JANUSZ KORCZAK BY SANDRA JOSEPH

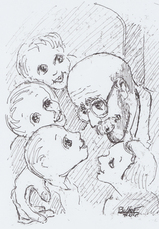

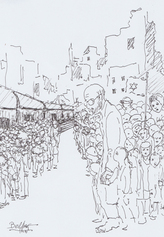

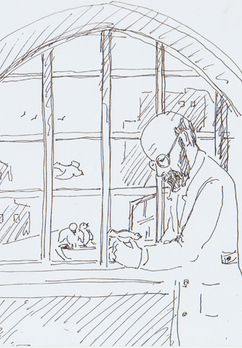

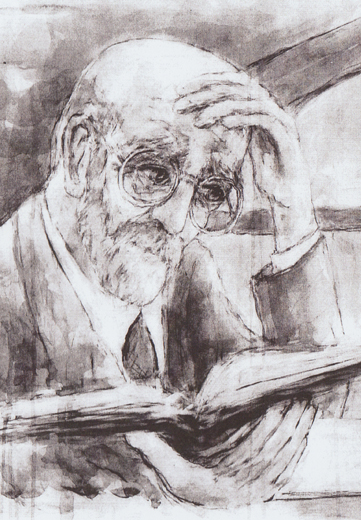

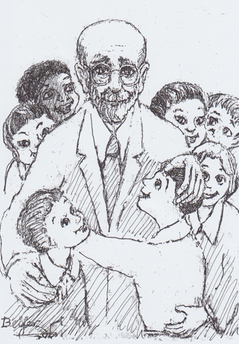

llustrations by Itzhk Belfer (one of Korczak's orphans)

“I am not here to be loved and admired, But to act and love. It is not the duty of people to help me, But it is my duty to look after the world, And the people in it.” J.K.

llustrations by Itzhk Belfer (one of Korczak's orphans)

“I am not here to be loved and admired, But to act and love. It is not the duty of people to help me, But it is my duty to look after the world, And the people in it.” J.K.

|

Janusz Korczak (1819 1942) the Polish Jewish physician, writer and educator, was a man who took his convictions and sense of responsibility so strongly, he was prepared to go to his death rather than betray them. A legend was born, when during the Nazi liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto, after rejecting countless attempts to save himself, offered by his many Polish admirers and friends, he led his two hundred orphans out of the Warsaw Ghetto onto the train that would take them to the gas chambers of Treblinka. This man, who had brought up thousands of such Jewish and Polish children refused to desert them, so that even as they died they would be able to maintain their trust in him and their faith in human goodness.

Most writings about Korczak begin by recalling this noble deed. However, the legend of the tragic and heroic death of this man, should not be allowed to obscure the richness of his life, and the way he lived it for both sides of the story shine with equal brilliance. “We were all surprised by Dr. Korczak’s instruction to gather in the X Ray lab”, one of his students recalls. The Doctor arrived bringing along a four year old boy from his orphanage. The X Ray machine was switched on and we see the boy’s heart beating wildly. He was so frightened so many strange people, the dark room, the noise of the machine. Speaking very softly, so as not to add to the child’s fears and deeply moved by what could be seen on the screen, Korczak told us “Don’t ever forget this sight. How wildly a child’s heart beats when he is frightened and this it does even more when reacting to an adult’s anger with him, not to mention when he fears to be punished.” Then heading for the door with the boy’s hand in his, he added, “That is all for today!” We did not need to be told any more everybody will remember that lecture forever.” |

|

Anticipating the field of juvenile justice, he spent one day a week, defending the destitute and abandoned street children, who were often given long jail sentences. “The delinquent child is still a child. He is a child who has not given up yet, but does not know who he is. A punitive sentence could adversely influence his future sense of himself and his behaviour. Because it is society that has failed him and made him behave this way. The Court should not condemn the criminal but the social structure.”

|

He was the director of two orphanages one for Catholic children and one for Jewish children where he lived in the attic of one of them, for most of his life, receiving no salary. In these he promoted progressive educational techniques, including real opportunities for the children to take part in decision making. For example his Children’s Court was presided over by child judges. Every child with a grievance had the right to summon the offender to face the Court of his peers. Teachers and children were equal before the Court even Korczak had to submit to its judgement. He envisaged that in 50 years every school would have its own Court and that they would be a real source of emancipation for children teaching them respect for the law and individual rights. His insights into children were unclouded by sentimentality, but were based on continuous clinical observation and meticulous listing and sifting of data. He was endowed with an uncanny empathy for children and a deep concern for their rights.

|

He was wise, loving and utterly single minded, without a thought for such needs as money, fame, home or family.

He founded a popular weekly newspaper, The Little Review, which was produced for and by children. “There will be three editors one oldster, bald and bespectacled and two additional editors, a boy and a girl.” Children and youth all over Poland served as correspondents, gathering newsworthy stories of interest to children. This was possibly the first venture of its kind in the history of journalism. He was well known and loved all over Poland as The Old Doctor which was the name he used when delivering his popular state radio talks on children and education. His soft, warm, friendly voice along with this natural humour won great acclaim and acquired an enormous audience. As one child listener reminisced: “The Old Doctor proved to me for the first time in my life, that an adult could enter easily and naturally into our world. He not only understood our point of view, but deeply respected and appreciated it.” |

Korczak spoke of the need for a Declaration of Children’s Rights long before the one adopted by the League of Nations in I924. He said: “Those lawgivers confuse duties with rights. Their Declaration appeals to goodwill, when it should insist. It pleads for kindness, which it should demand.” In I959 the United Nations produced a second Declaration on the Rights of the child, but this was not legally binding and did not carry a procedure to ensure its implementation. Significantly enough during the Year of the Child (I979) it was Poland who proposed that a convention should be drafted based on a text manifestly inspired by the teachings of Korczak. The Convention on the Rights of the Child was passed unanimously by the United Nations General Assembly on 20Ih November I989. It took countries over fifty years to hammer out the “Rights” that Korczak had already laid out in his books.

When UNESCO declared I979 “The Year of the Child” it also named it “The Year of Janusz Korczak to mark the Centenary of his birth. He has been compared to Mother Theresa, Martin Luther King and Socrates. Books have been written about his life and educational theories.

When UNESCO declared I979 “The Year of the Child” it also named it “The Year of Janusz Korczak to mark the Centenary of his birth. He has been compared to Mother Theresa, Martin Luther King and Socrates. Books have been written about his life and educational theories.

|

His own books have been published and republished in over twenty different languages, including Arabic and Japanese. (They are currently republishing all his educational works in Germany.) His work is studied at European universities and symposia are devoted to him. Films and plays have been produced about him. Schools, hospitals and streets have been named after him. Many monuments have been erected to honour him. He was posthumously given the German Peace Prize, Pope John Paul II said, that “for the world of today, Janusz Korczak is a symbol of true religion and true morality.” Yet he is hardly known in the English speaking world.

I hope that now as a result of my book 'Loving Every Child - Wisdom for Parents' (published by Algonquin Books) people in the United Kingdom will finally become aware of Dr. Janusz Korczak and his work. The book is a unique gift collection of his writings. Over I00 of his inspirational quotes are included together with a short biography. Most of the quotes are taken from “How to Love a Child” and “Respect for the Child”, books he wrote over fifty years ago but their insights and simple truths concerning children are as fresh and valuable today as they were then, for he was a man years ahead of his time. How many of us go down the road of parenthood alone, unprepared and frightened of losing our way in the multitude of different theories and ideas on childcare that bombard us everyday? We are afflicted by guilt because we didn’t do this or that that specialists say we should. We become confused when points of reference move almost daily. There are hundreds of books on childcare but they either concentrate on practical aspects or delve into areas of child psychology. How many of us need the simple inspiration and reassurance of being told and revel in the words: “I do not know and there is no way for me to know how parents unknown to me, can bring up a child unknown to me, in circumstances which are also unknown. I want everyone to understand that no book and no doctor can replace your own intuition and careful observation. For nobody knows your child as you do.” How often have we questioned children on some misdeed only to be confronted with a wall of silence? How comforted we would have been had we been guided by Korczak's simple wisdom: “The child is honest when he does not answer, he answers. He doesn’t want to lie, and he is too frightened to tell the truth. To my surprise I have stumbled upon a new thought. Silence is sometimes the highest expression of honesty.” By fate I fell into the world of Dr. Janusz Korczak whilst studying psychotherapy. Alice Miller, the renowned psychoanalyst, who achieved international recognition for her work on child abuse, on violence towards children and its cost to society, described Korczak as one of the greatest pedagogues of all time. I tried to find out more about this Dr Korczak, especially his theories concerning education and childcare. At libraries I drew a blank. I asked teachers, social workers, therapists and everyone I knew, but nobody had heard of him. |

|

This was the start of a journey that would change my life. He showed me two books by Korczak that had been translated into English. One was his famous children’s book “King Matt the First” and the other was his “Ghetto Diary”, written at the end of his life. “But what of his work on children” I asked. Sadly Felix shook his head. Very little had been published in English. I left with two treasured books “How to Love a Child” and “Respect for the Child” by Janusz Korczak but they were written in Polish.

I felt so frustrated. Slowly the idea dawned on me that there was no way I could enter into his world until the books were translated into English. A year later a biography on Korczak by Betty Jean Lifton was published called “The King of Children” as well as the brilliant film “XorczaW” directed by Poland’s greatest film director Andrzej Wajda. This convinced me even more. |

At last the translation was complete. I was amazed by what I read. He did not theorise, or give ready made answers, but presented the fruits of his experience in such a clear simple way. Almost like that of a child, direct but at the same time poetic, so that every reader could not help but be inspired. He acted as a guide on a journey into the mind of a child, offering insights we all need to learn in our modern society to get back in touch with the child within us all.

Korczak’s basic philosophy was his belief in the innate goodness of children and their natural tendency to improve, given the opportunity and guidance to do so. He felt that childhood was perceived as a preparation for a future life, when in fact every moment had its own importance one should appreciate the child for what he or she is and not for what he or she will become.

He believed in respecting and understanding the child’s own way of thinking instead of perceiving him or her from an adult’s point of view. The children in the orphanage lacked the emotional support of a parental figure and as a result were likely to assert themselves on the basis of anti social norms. Korczak’s approach was geared to prevent such development.

First and foremost, he knew that they needed to be able to trust and rely on adults. He therefore made it his goal to return to his children the very thing that adult society had deprived them of respect, love and care. This is what Korczak stressed in his lectures and books. That he achieved this is revealed by one boy who, on leaving the orphanage said: “If not for the home I wouldn’t know that there are honest people in the world who never steal. I wouldn’t know that one could speak the truth. I wouldn’t know that there are just laws in the world.”

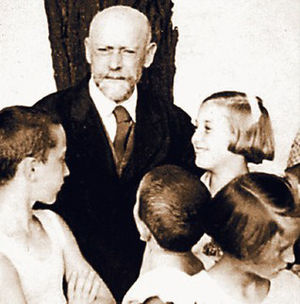

I went to Israel to interview his ‘children’ now in their seventies and eighties the few surviving orphans left in order to gain first hand knowledge of the man himself. Their faces lit up when describing Korczak. He was a loved father to them all, at a time when they desperately needed one. They all spoke of the feeling of warmth, kindness and love they felt in his company; about his smiling blue eyes and great sense of humour. I asked how they would explain to people who knew nothing of Korczak, why he was so important? One of them replied.

“It is difficult for me to explain to you in words the impact Korczak had on my life. He had so much compassion and a readiness to help all people. We used to say that Korczak was born to bring the world to redemption. What was so special about him was that he knew how to find a way to the child’s soul. He penetrated the soul. The time spent at the orphanage formed my life. All the time Korczak pushed us to believe in other people and that essentially man is good.

Korczak’s basic philosophy was his belief in the innate goodness of children and their natural tendency to improve, given the opportunity and guidance to do so. He felt that childhood was perceived as a preparation for a future life, when in fact every moment had its own importance one should appreciate the child for what he or she is and not for what he or she will become.

He believed in respecting and understanding the child’s own way of thinking instead of perceiving him or her from an adult’s point of view. The children in the orphanage lacked the emotional support of a parental figure and as a result were likely to assert themselves on the basis of anti social norms. Korczak’s approach was geared to prevent such development.

First and foremost, he knew that they needed to be able to trust and rely on adults. He therefore made it his goal to return to his children the very thing that adult society had deprived them of respect, love and care. This is what Korczak stressed in his lectures and books. That he achieved this is revealed by one boy who, on leaving the orphanage said: “If not for the home I wouldn’t know that there are honest people in the world who never steal. I wouldn’t know that one could speak the truth. I wouldn’t know that there are just laws in the world.”

I went to Israel to interview his ‘children’ now in their seventies and eighties the few surviving orphans left in order to gain first hand knowledge of the man himself. Their faces lit up when describing Korczak. He was a loved father to them all, at a time when they desperately needed one. They all spoke of the feeling of warmth, kindness and love they felt in his company; about his smiling blue eyes and great sense of humour. I asked how they would explain to people who knew nothing of Korczak, why he was so important? One of them replied.

“It is difficult for me to explain to you in words the impact Korczak had on my life. He had so much compassion and a readiness to help all people. We used to say that Korczak was born to bring the world to redemption. What was so special about him was that he knew how to find a way to the child’s soul. He penetrated the soul. The time spent at the orphanage formed my life. All the time Korczak pushed us to believe in other people and that essentially man is good.

He was an innovator of the educational system the first to reach the conclusion that the child had the same rights as the adult. He saw the child not as a creature who needs help, but as a person in his own right. All this was not just a theory he applied it in our orphanage.

There were no limitations in the framework of the rules. The child had the same rights as the teachers. For example, the Court’s first mission was to protect the weaker child against the stronger. The rules were based in such a way that only children had the right to serve as judges. The teachers did all the paper work. When the war broke out and I was starving and ready to do anything, I didn’t because something of Korczak’s teachings stayed with me.”

When I asked if history had been kind to him or was he really a man like this almost an angel? an elderly man with a broad grin answered: “In my opinion this was his very nature. Maybe it was because he had witnessed such poverty and hardship among abandoned street children when he was a doctor that gave him the strength to dedicate all his life as he did. I cannot remember any negative side to Korczak’s character, even now, when I myself am a grandfather and teacher, and understand more about children and their education. I honour the memory of a man who was my father for eight years; a man who has healed my physical and psychological ailments and who instilled a code of ethics that served me throughout my life.”

There were no limitations in the framework of the rules. The child had the same rights as the teachers. For example, the Court’s first mission was to protect the weaker child against the stronger. The rules were based in such a way that only children had the right to serve as judges. The teachers did all the paper work. When the war broke out and I was starving and ready to do anything, I didn’t because something of Korczak’s teachings stayed with me.”

When I asked if history had been kind to him or was he really a man like this almost an angel? an elderly man with a broad grin answered: “In my opinion this was his very nature. Maybe it was because he had witnessed such poverty and hardship among abandoned street children when he was a doctor that gave him the strength to dedicate all his life as he did. I cannot remember any negative side to Korczak’s character, even now, when I myself am a grandfather and teacher, and understand more about children and their education. I honour the memory of a man who was my father for eight years; a man who has healed my physical and psychological ailments and who instilled a code of ethics that served me throughout my life.”

|

I have shown Korczak’s writings to young people, parents, teachers and anyone whose life is involved with children. They all encouraged me to pursue this book validating the value of it’s message in today’s world. However, it was the children I have counselled over the years, many of whom had experience of abuse and neglect, whose reaction surprised me the most. Without exception they all wanted to know more about him.

If only my parents had read Korczak, they could have seen things from my point of view. Instead of feeling so isolated and misjudged, I could have quoted his words back to them. “Maybe then they would have understood me”. They agreed with Korczak that every school would benefit from a Court of peers which could help eradicate the social ills of today such as bullying and theft. They found it difficult to believe that fifty years ago he had set up a Committee (consisting of older children, himself and teachers) giving pupils a base to voice their ideas on improving the orphanage. They felt that if teachers listened to their opinions and valued their feelings in schools today it would help minimise truancy by creating a happier and more democratic environment. Korczak had always stressed the importance of ‘listening to and learning from children’. |